Can Life Evolve from Wires and Plastic?

In a laboratory tucked away in a corner of the Cornell University campus, Hod Lipson’s robots are evolving. He has already produced a self-aware robot that is able to gather information about itself as it learns to walk.

Hod Lipson reports: "We wrote a trivial 10-line algorithm, ran it on big gaming simulator, put it in a big computer and waited a week. In the beginning we got piles of junk. Then we got beautiful machines. Crazy shapes. Eventually a motor connected to a wire, which caused the motor to vibrate. Then a vibrating piece of junk moved infinitely better than any other… eventually we got machines that crawl. The evolutionary algorithm came up with a design, blueprints that worked for the robot."

The computer-bound creature transferred from the virtual domain to our world by way of a 3D printer. And then it took its first steps. Was this arrangement of rods and wires the machine-world’s equivalent of the primordial cell? Not quite: Lipson’s robot still couldn’t operate without human intervention. ‘We had to snap in the battery,’ he told me, ‘but it was the first time evolution produced physical robots. Eventually, I want to print the wires, the batteries, everything. Then evolution will have so much freedom. Evolution will not be constrained.’

Not many people would call creatures bred of plastic, wires and metal beautiful. Yet to see them toddle deliberately across the laboratory floor, or bend and snap as they pick up blocks and build replicas of themselves, brings to mind the beauty of evolution and animated life.

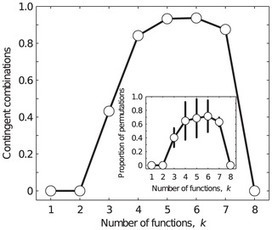

One could imagine Lipson’s electronic menagerie lining the shelves at Toys R Us, if not the CIA, but they have a deeper purpose. Lipson hopes to illuminate evolution itself. Just recently, his team provided some insight into modularity—the curious phenomenon whereby biological systems are composed of discrete functional units.

Though inherently newsworthy, the fruits of the Creative Machines Lab are just small steps along the road towards new life. Lipson, however, maintains that some of his robots are alive in a rudimentary sense. ‘There is nothing more black or white than alive or dead,’ he said, ‘but beneath the surface it’s not simple. There is a lot of grey area in between.’

The robots of the Creative Machines Lab might fulfill many criteria for life, but they are not completely autonomous—not yet. They still require human handouts for replication and power. These, though, are just stumbling blocks, conditions that could be resolved some day soon—perhaps by way of a 3D printer, a ready supply of raw materials, and a human hand to flip the switch just the once.

According to Lipson, an evolvable system is ‘the ultimate artificial intelligence, the most hands-off AI there is, which means a double edge. All you feed it is power and computing power. It’s both scary and promising.’ What if the solution to some of our present problems requires the evolution of artificial intelligence beyond anything we can design ourselves? Could an evolvable program help to predict the emergence of new flu viruses? Could it create more efficient machines? And once a truly autonomous, evolvable robot emerges, how long before its descendants make a pilgrimage to Lipson’s lab, where their ancestor first emerged from a primordial soup of wires and plastic to take its first steps on Earth?